Research Ethics Board Approved

Action Research Design prioritizing Qualitative Methods

We chose to apply an action research design because it has long been considered a method for improving practice (Koshy et al., 2010; Reason & Bradbury, 2008). Action research involves systematic enquiry into practice that incorporates action, evaluation, critical reflection, and changes to practice. It is focused on generating solutions to practical problems by engaging practitioners in research and the subsequent development of activities to improve educational outcomes.

The approach is participatory and democratic in nature (Carr & Kemmis, 1986) and was therefore intuitively appealing considering the principles and values that underpin our approach to learning outcomes and assessment.

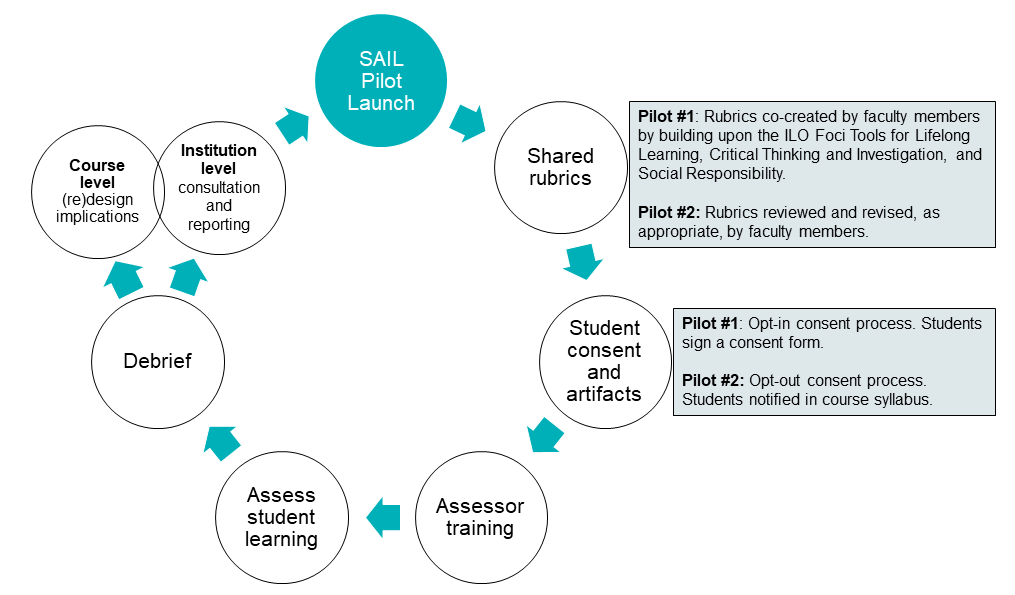

Action research is based on a series of action planning cycles, which typically involves some variation of planning, acting, observing, reflecting, re-planning, acting, and so forth (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2007). We adapted and expanded upon this series to include elements of educational development and community-building (Figure 1).

Below is a high-level summary of the steps in the SAIL action planning research cycle. Once the faculty-led communities of practice (“ILO Pods”) are formed for each of the ILOs being assessed the following steps are undertaken:

- Pilot launch including planning, preparation, and recruitment of faculty co-investigators.

- Development (or refinement) of shared institutional rubrics.

- Identification of appropriate student artifacts (course assignments) for assessment using the rubrics; and, notification to students of consent process.

- Faculty participation in Assessor Training delivered by an educational developer and quality assurance practitioner.

- Faculty assessment of peers’ assignments using the rubrics and rating sheets.

- Participation in focus groups (“Debrief”) led by SAIL Coordinators to determine the efficacy of the SAIL pilot project.

- Findings and recommendations drafted, reviewed, and publicly disseminated within and beyond the university.

- Faculty review and discussion regarding peers’ assessment and feedback of student learning; and modification of courses, as appropriate, based on feedback received.

In addition, we applied several qualitative approaches, which are listed below and described in greater depth at the following links:

- Focus groups (“Debrief”)

- Rubric-based descriptive assessments (“Assessor ratings”)

- Community consultations, including a mixed-methods survey and presentations to elicit feedback

Finally, we included some initial quantitative descriptive analysis of consent rates, which appear more prominently in the third action research cycle (Hoare et al., forthcoming). Note that SAIL was originally designed to incorporate a quantitative analysis of rubric-based assessor ratings to produce aggregate reports of student achievement of the ILOs; however, upon review of the qualitative data, we discovered limitations to interpreting the quantitative results in Pilots #1 and #2, and which were addressed in Pilot #3 based on findings from earlier pilots. To provide aggregate reports we assert that the reliability of the assessor ratings needs attention, including focused training as part of Assessor Training. We discuss this limitation further under “Cautionary Considerations for producing Aggregate Reports“.

Communities of Practice: “ILO Pods”

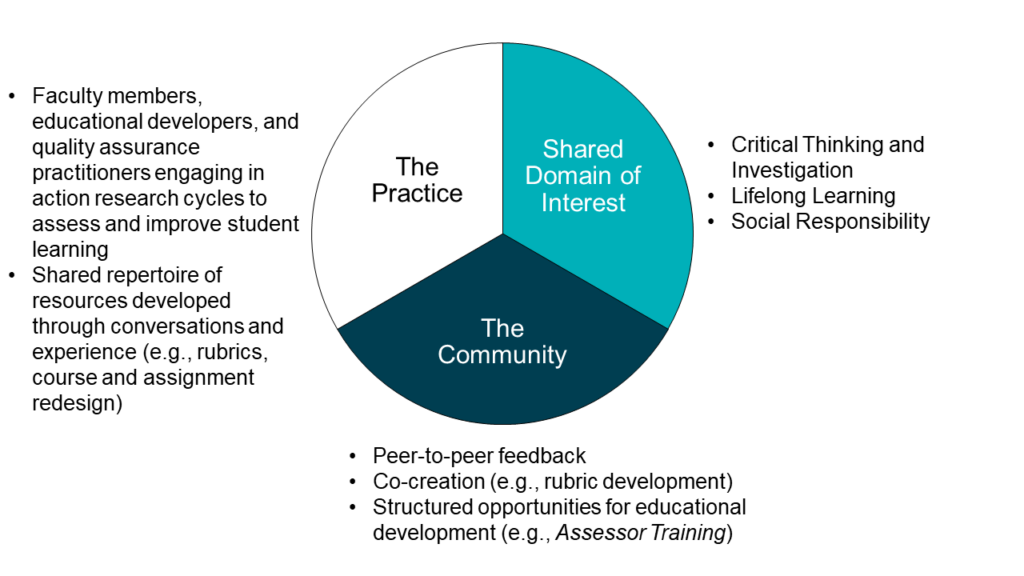

SAIL involves communities of practice (“ILO Pods”) of co-investigators who plan, discuss, and learn about assessment of institutional learning outcomes. A community of practice is formed when a group of people want to share common experiences and knowledge that are related to a particular area of expertise. Communities of practice are organized around what matters to people (Wenger, 1998). The concept originated in learning theory and has been used successfully to create learning systems in higher education (for example, see Bosman & Voglewede, 2019).

The three main characteristics of communities of practice are: 1) a shared domain of interest or competence that is distinct from other domains, 2) community engagement in shared activities that support relationship building and learning, and 3) the practice of the practitioners as the focal point of the activity (Wenger et al., 2002).

Figure 2 depicts the community of practice approach via interdisciplinary ILO Pods that was adopted to assess the degree of student achievement of institutional learning outcomes (sometimes referred to as graduate attributes or transferable skills).

When faculty members were asked what the greatest strength of the SAIL pilot was, they agreed that the opportunity to collaborate across disciplines with colleagues was the most valuable aspect of the pilot. Faculty valued the ILO Pod format (particularly the small group feedback) that was used to collectively assess student learning. They described collaboratively designing the rubric and reflecting upon assessment as highlights of the experience. Faculty found their peers’ interpretation of an ILO and how it was taught across multiple disciplines insightful; therefore, the interdisciplinary design of the ILO pods was perceived as an asset. Faculty appreciated the collaborative adventure as part of the co-creation of rubrics and missed the community when assessing assignments individually.

Co-Investigators

Faculty members participating in the research project join the research as co-investigators and contribute to the research design, implementation, and assessment of the effectiveness of the research methodology.

In 2020-21, a total of twelve faculty members engaged as co-researchers in SAIL and formed three ILO Pods (Social Responsibility n = 4; Lifelong Learning n = 4; Critical Thinking and Investigation n = 4). Six disciplinary perspectives were represented in the first pilot: tourism management, sociology, education, cooperative education, social work, and communications and media. In addition, faculty from the disciplines of biology and nursing participated in the development of the rubric for Lifelong Learning to ensure a diversity of disciplines were reflected in the development of each rubric.

In 2021-22, nine faculty members engaged as co-researchers and formed two ILO Pods (Lifelong Learning n = 4; Social Responsibility n = 5). Five disciplinary perspectives were represented in the second pilot: cooperative education, geography, business, social work, and sociology.

In 2022-23, four faculty members engaged as co-researchers and formed two ILO Pods looking at both Communication and Critical Thinking and Investigation. Four disciplinary perspectives were represented: social work, education, tourism management, and natural resource science.

Student Artifacts and Participation

Considering that the study aims to assess student achievement of ILOs, the study participants are students enrolled in courses taught by participating faculty members.

Student Consent

During the first iteration of SAIL, we piloted an opt-in process. Students enrolled in participating courses were invited to voluntarily consent to have one of their course assignments assessed by two faculty members who were not their course instructor. Student consent was sought within an ethics and privacy reviewed protocol to collect, anonymize, and assess one assignment for the pilot project. In addition, students’ instructors did not know who consented.

The overall student consent rate was 14.6 percent (46 out of 316 enrolled students). Response rates ranged from 2.4 to 50 percent across the participating courses. Given the low consent rate, we were not able to draw conclusions about the degree of student achievement of an institutional learning outcome. Instead, we focused our attention on the efficacy of the SAIL process, particularly the community of practice approach.

During the second iteration of SAIL, we piloted an opt-out process following an amendment to the REB proposal and consultation with the university’s Privacy Officer, Ethics Officer, and Student Caucus. The opt-out process involved the inclusion of a collection notice in the course syllabus, as well as verbal notice from the course instructor and/or SAIL Coordinators, and an announcement in the learning management system. The overall student consent rate was 98.9 percent (196 out of 198 enrolled students).

The third iteration followed the same consent process as described in the second cycle.

More information about the student consent process is available under Student Consent and Artifacts.

References

Bosman, L. & Voglewede, P. (2019). How can a faculty community of practice change classroom practices? College Teaching, 67(3), 177-187. https://doi-org.proxy1.lib.uwo.ca/10.1080/87567555.2019.1594149

Carr, W. & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research. Falmer.

Kemmis, S. & McTaggart, R. (2007). The action research planner: Doing critical participatory action research. SAGE.

Koshy, E., Koshy, V., & Waterman, H. (2010). Action research in healthcare. SAGE

Reason, P. & Bradbury, H. (2008) The SAGE handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice (2nd edition). SAGE.

Wenger, E (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W.M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice. Harvard Business Review Press.

Wenger-Trayner, E. & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Introduction to communities of practice: A brief overview of the concept and its uses. https://wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/