Writing the SAIL Practitioner Handbook provided an additional chance for us to reflect on SAIL. Numerous and sometimes unexpected opportunities for improving SAIL emerged during the writing process. We now find ourselves with an abundance of options for additional action research cycles, and welcome suggestions and collaborations from the broader SoTL community of scholars in Canada and globally.

Below, we briefly reflect on the ideal conditions for implementing a SAIL pilot project, how it might be used and for what purpose. We also describe notable opportunities for improvement, including further building community, consistency, and reliability among ILO Pod members; adapting assessment of institutional learning outcomes based on the intended purpose of the research; and engaging students as co-investigators.

Optimal Conditions for Implementing a SAIL Pilot

As described under Strengths and Limitations, we questioned the scalability of this model for learning outcomes assessment due to its resource-intensive design and use of a standardized rubric. Instead, we suggest that SAIL is optimally used under the following conditions:

- Voluntary engagement: Faculty are encouraged, but not required, to participate as this prioritizes the educational value of SAIL over a compliance-driven initiative.

- Immersive professional development: Faculty can commit a minimum of 35 hours during one semester to participate.

- Teaching-focused, collegial culture: To be successful, faculty must trust the process, their peers, and the SAIL Coordinators.

- Restricted to certain types of course-embedded assignments: Due to the use of a standardized rubric, SAIL is ideal for written and oral assignments, and poses challenges for some types of assignments, such as those that are primarily numerically-based (i.e., mathematics and statistics courses) and multiple choice exams.

SAIL is an ideal model for immersive faculty learning and development. Under the right conditions, SAIL is a high impact practice, engaging faculty in scholarly teaching and the scholarship of teaching and learning.

Build Community and Reliability

Communities of practice emerge as living, dynamic entities. We agree with scholars who view communities of practice as a process as opposed to an entity that can simply be put into place. In other words, communities of practice come into being over time and through learning, rather than existing at the initial onset. This “learning process view” (Pyrko et al., 2016, p. 390) is one of thinking together to explore a common interest.

The idea of ILO Pods as evolving facets of the SAIL Planning Cycle that ebb and flow as knowledge is shared, created, and reconsidered through a collaborative learning process is foundational to the SAIL methodology. Each ILO Pod takes on a life of its own: has different needs, strengths, tensions, questions, and solutions. It is the role and responsibility of the SAIL Coordinators to facilitate dialogue within the ILO Pods, gather resources to support their individualized learning needs, and to create the time and space for action research.

Across the first two SAIL pilots, faculty consistently craved more opportunities to collaboratively assess assignments, discuss assessor results and the patterns that emerged, and collectively generate solutions. Specifically, faculty noted a lag between the Assessor Training and the assessment of student artifacts, and a desire for a structured session to review the assessor ratings with their peers to discuss course redesign options.

In the future, we suggest modifying the SAIL Planning Cycle by designing more robust Assessor Training that incorporates the assessment of student learning and review of assessor ratings. Setting aside a full day for this session, and adding mid-assessment check-ins, and discussion of ratings could further collegiality and improve inter-rater interpretation.

Additionally, we suggest that future iterations of the SAIL Planning Cycle include a review of the shared rubrics both pre- and post- cycle, as ILO Pod members might contribute new insights with the experience they gained during the assessment of student learning.

Finally, there may be benefit in lengthening the duration of a pilot based on a three-semester SAIL Planning Cycle.

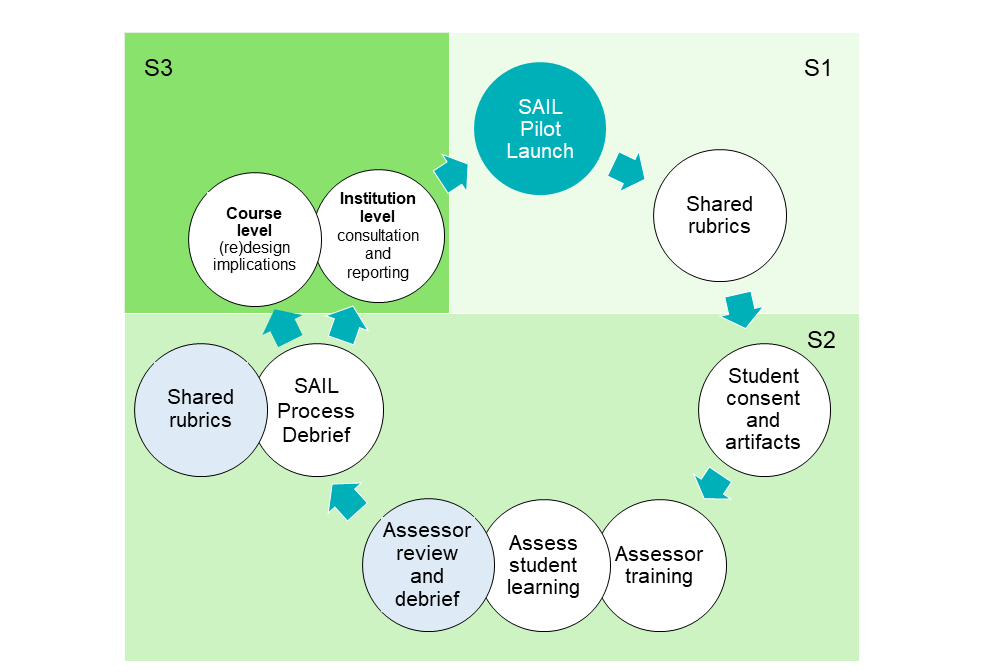

Figure 3 graphically depicts potential future considerations for revising the cycle.

During semester one (S1), faculty within an ILO Pod review their course and develop or refine a shared ILO rubric. During semester two (S2), faculty deliver their course, select an assignment to include in the pilot, and participate in a more robust Assessor Training session as noted above. During semester three (S3), SAIL Coordinators assist faculty in reviewing the assessor feedback and explore ways to apply what was learned to improve their practice.

Adapt Assessment of ILOs to Intended Purpose

Assessment of student learning can be conducted in a variety of ways, across multiple levels, and for different purposes. A common way to categorize types of assessment is indirect versus direct. Examples of indirect assessment at the program and institutional level include national surveys that document student perceptions of self-reported learning; GPA and student retention, persistence, and graduation rates; or employer perceptions of graduates’ career-preparedness. Examples of direct assessment include student performance on standardized tests that assess writing, numeracy, and critical thinking; rubric ratings for course-embedded assignments in general education courses; or pass rates on licensure or certification tests. A relatively comprehensive listing of examples of direct and indirect evidence of student learning at the course, program, and institutional level is available in Suskie’s (2009) Assessing Student Learning: A Common Sense Guide. A handout is also available here: Direct and Indirect Assessment (Suskie, 2009) (PDF)

Through SAIL’s systematic process of enquiry, we expanded our understanding of assessment of student learning outcomes. We questioned the purpose and value of different assessment practices. We investigated how different practices contribute to educational development, teaching and learning, and institutional knowledge.

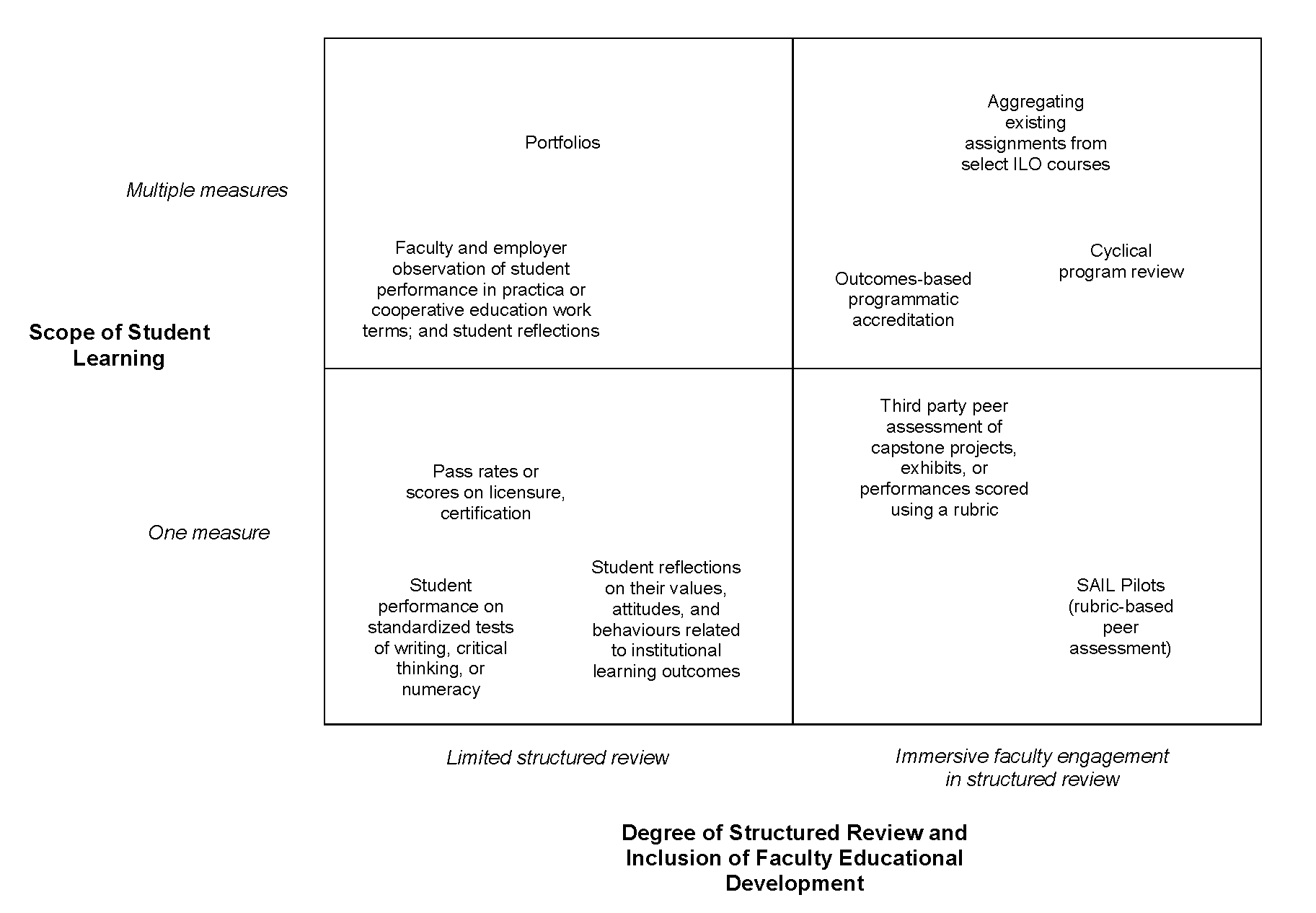

SAIL’s learning process approach of thinking together, helped us to develop an Institutional Learning Outcomes and Assessment Ecosystem (Figure 5) that compares the scope of student learning and the degree of faculty engagement in structured review of student learning. The LOA Ecosystem explores examples of direct assessment at the institutional level. Note that the LOA Ecosystem is not intended to provide a comprehensive listing of all types of assessment (instead see Suskie, 2009), but rather to explore the scalability, generalizability, and resource requirements for implementing different types of assessment methods.

When planning assessment of institutional learning outcomes (ILO), programs or institutions could consider employing a combination of approaches with different approaches combined to assess specific outcomes. For example, a program or institution might leverage a SAIL approach for emergent development of courses with a shared understanding of an ILO like Lifelong Learning, while utilizing aggregated grading from select required courses’ exam questions to assess knowledge, and capstone projects to evidence skills acquired from a range of experiences.

Please note that, based on our experience, we do not recommend the use of standardized testing for assessing institutional learning outcomes. Standardized tests are believed to be incongruent with the university’s structure and culture, namely the incredibly diverse educational programming, collegial and teaching-focused culture, and the principles that guide learning outcomes and assessment. When not embedded in the curriculum, standardized tests offer limited educational value to students and faculty. Research has shown that students are much more motivated to do well when assessments are linked to the curriculum, when their efforts count for marks, and when their instructors can articulate the relevance of the assessment method to the course content and beyond the classroom (Deller et al., 2018).

Engage Students as Co-Investigators

The capacity to engage student as co-investigators in a SAIL pilot exists and merits future exploration. As places of teaching and learning, universities benefit from structures that promote co-curricular activities that enhance student learning, such as undergraduate research. Scholars suggest that this strength can be utilized to support the implementation of qualitative research methodologies (Fine, 2017; van Note Chism & Banta, 2007).

Emerging research on pedagogical partnerships further suggests that engaging students as partners in quality assurance and educational development can position students as experts in their own learning and development. Ryan (2015) argued that “the student has the ability to see the situation from the learner’s perspective” (p. 8). By complementing the faculty and institutional perspective of quality assurance with a student perspective, we may learn valuable insights into the lived experiences of students (Tinto, 1994).

Limited student engagement in quality assurance processes is common in Canada. A recent report published by the Curriculum Working Group Meeting of the Council of Ontario Educational Developers (Heath et al., 2021) showed that current practices “fall short of recognizing the centrality of [student] perspective[s] and experience[s] of the working program” (p. 14). Students invest a significant amount of time and money in their education and have a special interest in the quality of their educational experience (Alaniska et al., 2006).

In Ontario there is growing recognition that engaging students as meaningful partners in quality assurance processes can further enhance the effectiveness of those processes. For example, in 2019 Humber and Centennial Colleges hosted the first Student Voices in Higher Education: Quality Assurance Perspectives and Practices Symposium (Burdi, 2019).

To engage students as co-creators of institutional knowledge as part of a SAIL pilot, students can be hired as research assistants, join an ILO Pod, participate in all steps of the SAIL Planning Cycle, contribute, and gain invaluable learning. The added support of research assistants could alleviate time constraints placed on faculty, increase the sample size selected for assessment, and provide feedback to faculty for review and contextualization.

References

Alaniska, H., & Eriksson, G. (2006). Student participation in quality assurance in Finland. In H. Alaniska, E. A. Cadina, & J. Bohrer (Eds.), Student involvement in the processes of quality assurance agencies, (pp. 12-15). European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education.

Burdi, A. (2019). Listening to student voices in higher education. Humber Today. https://humber.ca/today/news/listening-student-voices-higher-education

Deller, F., Pichette, J., & Watkins, E. K. (2018). Driving academic quality: Lessons from Ontario’s skills assessment project. Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. https://heqco.ca/priorities/learning-outcomes/learning-outcomes-assessment-consortium/driving-academic-quality-summarizes-lessons-from-heqcos-learning-outcomes-assessment-consortium/

Fine, M. (2017). Just research in contentious times: Widening the methodological imagination. Teachers College Press.

Heath, S., Wilson, M., Groen, J., & Borin, P. (2021). Engaging students in quality assurance processes: A project of the COED Curriculum Working Group. http://www.coedcfpo.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Engaging-Students-in-Quality-Assurance-Processes-Final-Report.pdf

Pyrko, I., Dorfler, V., & Eden, C. (2017). Thinking together: What makes communities of practice work? Human Relations, 70(4), 389-409. http://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716661040

Ryan, T. (2015). Quality assurance in higher education: A review of the literature. Higher Learning Research Communications, 5(4), DOI:10.18870/hlrc.v5i4.257

Suskie, L. (2009) Assessing student learning: a common sense guide (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Tinto, V. (2017). Through the eyes of students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 19(3), 254-269.

van Note Chism, N. & Banta, T. W. (2007). Enhancing institutional assessment efforts through qualitative methods. New Directions for Institutional Research, 136, 15-28. https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.228